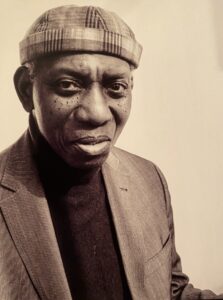

Photo: Arthur Elgort

Yusef Komunyakaa – Laureate of The Zbigniew Herbert Award 2021

Yusef Komunyakaa was born James William Brown, on April 29, 1947, in the small agricultural town of Bogalusa, Louisiana. The descendant of a large Afro-American family, a carpenter’s son, he would later admit that his father’s craftsmanship and attention to detail, as he measured plank sizes many times over – so that everything fitted, influenced his artistic practice, the need to rework, edit in an unstinting persistence at achieving perfection.

Once an adult, he changed his surname to Komunyakaa – his grandparent’s name, who came to America as stowaways on a ship from Trinidad. The poet recalls how thanks to his grandparent’s great religiosity he discovered the power of language. Listening to them gave him an understanding of how biblical phrases and their melody shape speech. Radio, that played a central role in the Komunyakaa family, proved to be another element of that formative experience, as it spurted out jazz and blue’s sounds all day long. As he listened, so the boy became engulfed in a world full of music, arranging vocals in his head in non-existent languages…

The change of name was obviously a symbolic gesture, an ostentatious signing up to the Afro-American cultural tradition, a tradition of generations of slaves, who gradually regained their freedom. The years of Komunyakaa’s childhood and youth was still a time of racial segregation in the American South, when Afro-American residents could, for example, only occupy designated seats on buses, and when there were still murders, and acts of terror perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan. “Nobody Knows My Name”, by James Baldwin, a classic novel of African-American literature, was one of the most important books of Komunyakaa’s youth.

The future poet departed Bogalusa, on obtaining his high-school diploma, moved to Arizona, then Puerto Rico to end up joining the army in 1969, and what was to be a life changing experience. Sent to Vietnam as a war correspondent, then appointed managing editor of the »Southern Cross«, an army publication, he took with him an anthology of contemporary American poetry, that he read and re-read, becoming ever more aware that he would not be an essayist or writer of prose, but a poet.

On his return from the war he studied at the University of Colorado, first majoring in sociology and English, and then Mastering in Creative Writing. It was also at that time that he began to write, inspired amongst others by French Surrealism, as well as a newly developing so

called “negritude” poetry movement, begun by Aimé Césaire. He published his first two poetry books at his own expense, and it wasn’t until his third volume, that publishers and critics took an interest. The work was titled “Copacetic” (1984), which as Komunyakaa’s polish language translator explains – in jazz slang translates as a work “totally satisfactorily composed”.

The link to jazz did not only apply to that volume. Jazz and blues music is for Komunyakaa a subject source for his poems (as in the case of a poem about Charles Parker), and an inspiration to write opera librettos, or poems motivated by works of music (such as in the case of Australian jazz vocalist Pamela Knowles). But critics have, above all else, often noted how the build and rhythmic structure of many of Komunyakaa’s works are so reminiscent of jazz music, with all its complexity and improvisation. The noted Katarzyna Jakubiak wrote about this phenomenon:

In jazz pieces, melody lines pleasing to listeners ears are intertwined with hard-to-digest dissonances, whilst familiar motifs grow into a controlled chaos of sounds. Similarly, in Komunyakaa’s poetry, “pretty” and understandable fragments lie adjacent to overly complex images, whilst motifs known from the classics of high culture or popular culture succumb to conscious disassembly and alterations.

And she continues:

Komunyakaa imitates the openness and flexibility of jazz through an open form that allows the reader to become a poem’s co-author. Describing his creative process, Komunyakaa admits that when working on a text, he always looks in his poems for “doors to remain open” – places that are deliberately structurally “loose”. It is exactly through these “doors” that the reader can enter the poem and begin his own improvisation.

Komunyakaa himself said: “the reader does not necessarily need to know what a given poem means, but above all else, he must feel something; like listening to music. We can achieve remarkable clarity of thought through mere feeling”.

Apart from references to the structure of jazz, two other key aspects of Yusef Komunyakaa’s work are most often identified: a deep immersion in Afro-American culture, recounting the fate of millions, often nameless African Americans, first slaves, and subsequently

“second class” citizens. And also a poetic testimony to the Vietnam war, this war, which for a whole generation of Americans had a significance comparable to that of The Second World War; a trauma, but also of defined ethical and political choices, of a way of perceiving the world.

For the first aspect “Neon Vernacular” (1994) , winner of the Pulitzer Prize, had the greatest meaning. To once again quote Katarzyna Jakubiak:

The collections title perfectly, precisely reflects the complexity of the concept. In the context of African-American culture, the word vernacular has a variety of meanings. It was originally used to describe a slave born on his master’s land. With time, the word began to denote a specific Afro-American English language dialect, as well as a specific Afro-American culture, based on both folk and “street” traditions (e.g. black ghettos). In such a juxtaposition the use of the word ‘neon’ equates to an intelligent game with the prefix ‘neo’. So in Komunyakaa’s volume we are in effect dealing with neo-culture and neo-language, but also, literally, with post-modern neon culture.

It should be emphasized that Komunyakaa’s poetry is not confined to one culture, on the contrary – it combines references to American, African, European and Asian traditions.

Concerning the second aspect, the crowning achievement was a collection titled “Dien Cai Dau” (1988), which in Vietnamese means “crazy” – being a description of the American soldiers fighting there.

Yusef Komunyakaa lives in the state of New Jersey, and is currently Distinguished Senior Poet in New York University’s graduate creative writing programme. Apart from the Pulitzer Prize, his honours also include the Wallace Stevens Award, Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, the William Faulkner Prize (awarded by the Université de Rennes), as well as a prestigious stipend from the National Endowment for the Arts. His most recent poetry works include “The Emperor of Water Clocks” (2015) and “Everyday Mojo Songs of the Earth: New and Selected Poems” (2021).

Herman Melville, Marguerite Duras, Pablo Neruda, Derek Walcott, Federico García Lorca, Gwendolyn Brooks and Robert Hayden number amongst the writers he most admires.

From the point of view of admirers of Zbigniew Herbert’s poetry, it is worth noting that in his poems Komunyakaa often used characters, lyrical personalities – not unlike the Polish poet, creator of the “Elegy of Fortinbras” or the figure of Mr. Cogito.

Komunyakaa Polish visits include his stay in 2005 when he took part in American-Polish poetry meetings, reading his works alongside Wisława Szymborska. Janusz Szuber, recently deceased, wrote a poem “To Yusef Komunyakaa”, which can be found in his volume “The Crowing of Roosters” [“Pianie kogutów”].

The abovementioned Katarzyna Jakubiak numbers among translators of Yusef Komunyakaa’s works into Polish. Znak, a Polish publisher, will make available a selection of Komunyakaa’s poems translated by her under the title “Hour” [“Niebieska godzina”] next month when the poet will receive The International Zbigniew Herbert Literary Award.

***

Comments about Yusef Komunyakaa include:

Tomasz Różycki: “he is undoubtedly one of the most original and expressive poets of our time. His voice, combining the explicit experiences of a black man born in a small town in Louisiana in the American South, a veteran of the Vietnam War, brought up in the jazz and blues tradition, writing about the most painful experiences of modern life in the USA, is all at once universal and deeply human, in how it invokes the traditions of many cultures, whilst Greek gods and jungle deities turn out to be his almost tangible interlocutors.

It is poetry of great sensual energy, coming straight from the body, and touching on matters of the world and the universe, partaking part in a spiritual community, where the singular is combined with the universal in a characteristic jazz syncopated rhythm. In these poems the biblical Isaac meets up with Dizzy Gillespie, Pablo Neruda with At-Thinnin, Caliph of Baghdad, and Billie Holiday with Ezekiel and Hesiod. And yet, Komunyakaa remains authentic and passionate, there is no pose in this poetry. It is a poetry of communing spirits raised with the rhythm of drums, a poetry of dance and love; a great song in honour of life and existence.”

Edward Hirsch: “Yusef Komunyakaa is an African American poet of international stature. Like Zbigniew Herbert, he is an avant-garde classicist with a strong »tablet of values«.” Komunyakaa writes out of his childhood, growing up in the American South, his stint in Vietnam, and his experiences in a wide range of cities, from New Orleans, Louisiana to Trenton, New Jersey. One can read his work as a lifelong quest for peace, freedom, and social justice. His artistry is unique. Deeply indebted to Black music and history, he has invented a jazzy poetic idiom, what he calls “neon vernacular,” that reaches peaks of biblical eloquence.”

Katarzyna Jakubiak: “the most distinctive feature of this poetry are its rich, emotional images. Komunyakaa often jokes that »innate surrealism« lies at the root of his work, an unbridled imagination that developed during his childhood, one influenced by both landscape and the political atmosphere of the American South”.

Jerzy Illg: if someone were to ask me what impressed me the most in his poetry, I would point out three phenomena. Firstly, the poetry is fascinatingly musical, organically linked to jazz and the blues. Komunyakaa not only writes about great jazzmen, but also gives his poems swinging rhythms, thanks to which they pulsate with the subcutaneous pulse uniquely characteristic of black music. In addition, he willingly recites his poems in the company of jazz musicians.

Secondly, I had never read such moving and real poems about war. Poems from the volume titled »Dien Cai Dau« [‘crazy’ in Vietnamese] enable the reader to experience the nightmare of war, almost firsthand, take him into the trenches, the damp jungle to where death is hidden behind every fern leaf. Dread, fear and cruelty are transformed into the purest poetry.

Finally thirdly, numerous polonicas may surprise, indeed encourage Polish readers to take an interest in this poetry. Komunyakaa was connected with Poland in a very personal way, he visited our country on numerous occasions – hence the pictures of Warsaw streets or the Copernicus hotel in Cracow. More importantly – both the Racławice Panorama and Hasior’s sculptures benefited from a poetic testimony, whilst Jagiellonian University’s murdered professors and anonymous victims of the Holocaust, were duly commemorated”.